The Custom Mill, Its Community, and Its Significance by Leslie Hawkins Meadows

The gristmill and the church were usually the first two buildings constructed in any new American settlement because they provided vital services. The church protected the settlers’ souls, and the mill ground the flour and meal for a family’s bread. Without an easily accessible mill, farmers would have been reluctant to move to a new area because there would be no way to guarantee a steady supply of food products. Once the mill and the church were constructed, they often attracted more settlers, encouraging a community to grow and develop. Because their services were often considered valuable selling points to a property, advertisements in early America frequently mentioned when a mill or church were near a farm for sale. For example, John Mackey of North Milford, Maryland, advertised in 1783, “TO BE SOLD, A PLANTATION, pleasantly situated in North Milford hundred, Caecil [sic] county, Maryland, convenient to a gristmill, and several places of worship of different denominations… containing 200 acres.”[1] Town promoters and the general populace considered gristmills a public utility, and used their availability to attract new settlers to a developing region of the country.[2]

A blacksmith shop, distillery, or sawmill often emerged next to a gristmill. A community store also quickly followed. These stores, in addition to selling goods imported into the area that could not be readily produced at home, sold products produced at the mill, including corn meal ground from the miller’s toll, and whiskey produced at the distillery. “Through all these services a mill strengthened not only its economic base but its position as a community center.”[3] Mills drew in farmers and their families, as well as those who worked in the nearby shops and trades: millers, blacksmiths, distillers, storekeepers, and many more.

Most local, custom gristmills would have at least ground cornmeal. Producing stone ground cornmeal is a relatively simple process that can be done with any kind of rock fashioned into grinding stones. Granite, which can be found all along the eastern seaboard of the United States, would have been the preferred stone; but any hard, grey rock would have been considered sufficient. In order to make cornmeal, the farmer must let the corn dry in the field before harvesting it. After that, the farmer needed to shuck and shell his corn before carrying it to the mill. After the miller weighed the grain brought to him, he entered the corn into the system, where it would be carried to a screen cleaner to remove any harvest trash that may be mixed in with the kernels. The corn then went through the grinding process. The millstones were cut into patterns or grooves that continuously ground the kernels, as the centrifugal force of the moving upper grinding stone gradually pushed the meal to the outer edge of the stones. Once the meal exited the millstones, the casing surrounding the stones forced the meal into a spout leading to a receiving bin, where the ground meal collected. After the corn was ground, the meal needed to be sifted or bolted, but was otherwise ready for consumption.

Producing stone ground wheat flour required much more work because most consumers desired the purest, whitest flour possible. The process was simplified in 1790, when Oliver Evans received the third U.S. patent ever issued for his automatic flour milling system that incorporated elevators, augers, and a totally new device, the hopper boy. After the wheat was harvested from the field and the wheat berries separated from the stalk through a threshing and winnowing process, the farmer brought his wheat berries to the mill. In Evans’ system, the berries went through the cleaning process twice, once through a rolling screen cleaner to remove harvest trash, and then a second cleaner, commonly called a scourer or smutter, to remove finer particles and dust. After being cleaned, the wheat berries were then ground in a similar way as the corn. Wheat, however, required a specific kind of millstones, made of French burr, a type of fresh-water quartz found only in France. French burr has been the preferred stone for producing stone-ground wheat flour since the 1300s because of the consistency of the grain in the rock, and the way it cuts the berries’ shell without pulverizing the husk into the flour. After being ground, the miller had wheat meal, a warm, damp product, not wheat flour. To prepare the wheat meal for sifting, the meal was cooled and dried. A set of elevator buckets carried the meal to the upper floors and dropped it on the floor. At this point, a mechanized rake called a hopper boy slowly cooled and dried the meal. Afterward, the meal went to a bolter, a cylinder covered in different grades of silk cloth to sift the meal into three grades of flour: fine, middlings, and sharps.

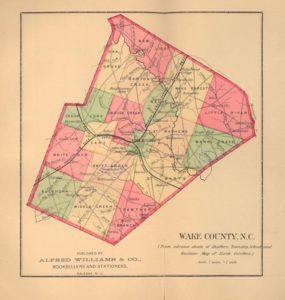

Traditionally, all mills would have run off of either animal or water power. Gradually during the 19th century, using steam to power turbines became more and more common, not just for merchant mills, but for custom mills as well. Several of Wake County’s mills ran off of a turbine system, including Lassiter Mill and the mill at Lake Myra. Others, such as Yates Mill, continued to use only water power, likely either because of the cost of the new technologies, or their water sources provided sufficient power to run the mill. The transition to turbines took place for several reasons. Steam was a more efficient power source than water, and steam power freed the miller from dependence on a stream and millpond that might run dry in the hot summer months. Moreover, if more than one mill stood along the same stream, millers downstream were dependent on those upstream to release water held by their dam.

Owning and operating a gristmill was a private business. Individuals invested in the construction of gristmills because they saw it as a means to make money and to provide for their families. But, mills also fulfilled a public good by supplying a service everyone in the community needed to survive. As a result, state governments often found it necessary to enact laws regulating the millers’ business practices. For example, a colonial North Carolina law of 1758 made all mills accessible to the public and required a license from the county court in order to dam a waterway to build a mill. The newly formed state of North Carolina reaffirmed this law in 1777, stating, “Every grist or grain mill, however, powered or operated, which grinds for toll is a public mill.”[4] All gristmills came under the public domain because most colonies and states felt laws regulating their location and the ways millers conducted business were necessary to protect public interest in available waterways, as well as to protect the business interests of the public and other mill owners in the area.

Because access to ground grain was necessary for a community’s survival, the North Carolina’s legislature had to guarantee the availability of millers to serve the community once the mills were constructed. One threat to that availability was the requirement for men ages sixteen to sixty to serve in the in the local militia. However, “several categories of people were exempt from military duties, including ministers, … practicing attorneys and physicians, former military officers, the clerk of court, and citizens operating public mills or ferries. These were all considered essential services.”[5] Without individuals such as ministers, physicians, and those who operated custom mills and public ferries, society would not have been able to properly function. Thus, state legislatures felt compelled to ensure those services would always be available, regardless of the state’s other needs, even military service. As a result, millers, but not mill owners, were exempted from military service in colonial and early national era.

Another North Carolina law regulated the payment millers could charge their customers. Custom mills provided valuable services to their neighbors, and their customers benefited greatly by having one nearby. This tight sense of interdependence, however, sometimes led to accusations of dishonesty and exploitation. The miller’s dishonesty can be traced back even to the Middle Ages, when Geoffrey Chaucer, in his “Miller’s Portrait” described the miller, “He was a jangler and a goliardese / And that was most of his sin and harlotries. / Well could he stealen corn and tollen thrice, / And yet he had a thumb of gold pardee.”[6] Chaucer’s miller represented what many believed all millers to be: dishonest, garrulous, thieves. Traditionally, millers working at custom mills did not accept cash as payment for their services; instead, they took a miller’s toll, or a portion of the grain the customer brought to the mill. Most states, therefore, established laws regulating the amount of toll a miller could collect for his services.

In North Carolina, the law specifically instructed millers to “grind according to turn, and shall well and sufficiently grind the grain brought to their mills, if the water will permit, and shall take no more toll for grinding than one-eighth part of the Indian corn and wheat… and every miller and keeper of a mill making default therein shall, for each offense, forfeit and pay five dollars ($5.00) to the party injured.”[7] This statute insured mill customers were not cheated out of their meal or flour, and millers did not show preference toward one customer over the other. While other forms of payment existed, such as cash or barter, the miller’s toll was generally the preferred method of payment. In North Carolina, “From earliest settlement, millers customarily received a portion of the grain for their services. A census taker in northeastern Wake County reported in 1860 that eleven grist- and flour mills in his area ground corn and wheat ‘only for toll & do not buy & sell but very little, and with one or Two exceptions the owners could give me no correct information concerning the Amount annually realized from the investment.’”[8] Collecting a miller’s toll allowed the miller to either feed his own family, or to sell or trade for items the family needed but could not produce on the homestead.

The location of a new mill was not always an independent decision made by the miller. Wake County is lucky in the fact that it lies along the fall line of the Little and the Neuse Rivers, providing a natural drop in its creeks and streams. For these streams in Wake County, the fall line means an abrupt increase in downhill gradient, as well as the narrowing of the creek bed, and the creation of rapids and waterfalls. Early settlers favored sites along fall lines for the construction of mills and dams because an elevated water source, as well as the natural narrowing of the waterway, made it easier to build a dam. These sites in Wake County can be easily identified because of the outcroppings of Falls Leucogneiss, a type of metamorphic rock. Historic mills in Wake County situated along the fall line include Yates Mill, Lassiter Mill, and a succession of mills constructed along the Falls of the Neuse River.[9] A second determinant for the location of mills was the availability of a power source, specifically creeks and streams. Thankfully for early settlers, Wake County has a plentiful supply of streams that offer a number of good potential mill sites. As a result, custom mills served communities scattered across the county, rather than having all of the mills in the county collected around only one or two sources of water.

Proposals for constructing new mills also often had to be approved by local and state governments to determine if the new mill would fill a void in the local community without hurting previously constructed gristmills and other businesses already located in the area. A variety of concerns might prevent government officials from approving a new mill. Some potential mill sites were rumored to produce sickness among nearby residents. For example, in 1849, William Boylan, a Wake County resident, prominent businessman, and mill owner himself, answered a number of questions from the Wake County courts about whether or not a milldam could and should be rebuilt on Walnut Creek near downtown Raleigh. The court was concerned that “bilious fever and ague” or malarial illnesses might return when the millpond was reestablished. The mill in question had been previously shut down and its millpond drained after it was believed to be the source of an epidemic in and around the city of Raleigh several years earlier. Boylan reported to the court “that he does not suppose the erection of said Mill would produce irreparable mischief to the relators [sic], but he should have some fear of sickness at this residence.”[10] He did, however, also state that the reconstruction of the mill “would be of public convenience to the citizens of the town and neighborhood.” Others, however, disagreed with Boylan’s assessment of the new mill’s benefits. R.N. Seawell stated that “he thinks that the public necessity does not require the erection of a mill there; but… it would be of convenience in seasons of drought, to the vicinity of the place, and perhaps to some citizens of Raleigh; although as to most of the citizens of the town, … it would be of not much public convenience at any season.”[11] Seawell believed that Wake County already had a sufficient number of mills to serve the needs of the community in question and that the proposed gristmill was unnecessary.

Just because a gristmill provided a valuable service to the local community did not always mean that everyone welcomed the new mill. One man’s energy source for a gristmill was another man’s navigation route or fishing spot. Some residents expressed concern that the construction of the milldam along a navigable river or stream would impede the transport of cash crops to markets downstream. This dam, these farmers argued, would cause more damage to their families’ income than the extra effort required to reach a more distant mill.[12] Similar problems arose when the construction of a milldam threatened to prevent the annual migration of fish through the regions’ rivers. Hindering local fishing was a threat to the poorer inhabitants of an area, because fish from local waterways formed a large part of their subsistence.[13] Even though gristmills and the milldams that served them provided a source of food and offered to make the lives of area residents easier, their practicality and importance had to be considered in comparison to the other means of livelihood in the community.

More than seventy mills were hard at work in Wake County during the 1870s, the heyday of water-powered grist milling. During the next thirty years, however, consumer demand changed. New technology improved the grinding and refining process of flour and cornmeal production, creating a finer, purer product. Americans, desiring the finest white flour and cornmeal available, often preferred products from the newer, bigger mills to the coarser products generally available from the traditional local gristmill. Developments in national transportation, including the widespread expansion of the railroad at the end of the 19th century and the introduction of the automobile during the beginning of the 20th century, made the shipment of the new products faster and more cost-efficient. Around the turn of the 20th century, farmers generally found it easier and cheaper to grow a cash crop and purchase their flour and cornmeal from the store rather than to grow the wheat and corn for themselves.

Of all of the mills that once served Wake County, only one, Yates Mill, remains standing today. The others have passed into history, disintegrating as robberies, fires, the elements, and time have taken their toll. However, evidence of the other mills and the important functions they filled in society still exists. Old milldams, grinding stones, and machinery can still be found throughout the county. Even street names like Edwards Mill Road, Yates Mill Pond Road, or Lassiter Mill Road continue to be subtle reminders of where the old mills once stood, and the significance they held for the local community. In fact, the location of mills often determined the location of roads, and the availability of roads in turn helped determine the location and success of mills.

The three mills discussed here, however, have all managed to find new life in the modern Wake County community. Yates Mill is the centerpiece of a research and recreational park owned by North Carolina State University and maintained by Wake County. A local, non-profit group restored Yates Mill and is responsible for the continued maintenance and interpretation of the mill. The Lassiter Mill site is on the City of Raleigh Greenway System and is marked with a plaque briefly describing the mill site’s long history. While the mill itself is gone and homes now surround the site, the milldam, part of the mill’s foundation, and a cement sign for the Lassiter Lumber Company still stand as reminders of the thriving mill businesses that once existed along Crabtree Creek. The mill at Lake Myra collapsed, but the rubble remains, as well as several of the other buildings; the store, built when Lake Myra served more as a recreational facility than a mill site during much of the 20th century, still stands. A private family currently owns the property; but the Wake County department of Parks, Recreation, and Open Space is in the process of developing a plan to purchase the property and make a county park so the community may use Lake Myra for recreation once again.

1 John Macky, The Pennsylvania Gazette 13 August 1783.

[3] Jean Anderson, “A Community of Men and Mills,” Papers from the Seminar on Waterwheels and Windmills Held in Durham, NC, July 1978, in the Bicentennial Year of West Point (Durham, NC: The Association for the Preservation of the Eno River Valley: Friends of West Point, 1979) 32.

[4] NC Laws, Chapter 73, Article 1-1, 1777.

[5] Elizabeth Reid Murray, Wake: Capital County of North Carolina (Raleigh, NC: Capital County Publishing Company, 1983) 35; N.C. Laws, Chapter 1, 1746 and N.C. Laws Chapter 4 1749.

[6] In this passage, Chaucer was saying that a miller is loud and a joker, as well as dishonest. More specifically, Chaucer accuses many millers of taking three times the allotted toll for his services. The final line insinuates that an honest miller had a thumb of gold, possibly meaning that there is no such thing as an honest miller. Geoffrey Chaucer The Portrait of the pilgrim Miller from the General Prologue. The version quoted here can be found at http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/webcore/murphy/canterbury/4miller.pdf accessed 2 March 2008.

[7] NC Laws, Chapter 73, Article 1-2, 1777.

[8] Kelly A. Lally, The Historic Architecture of Wake County, North Carolina (Raleigh, NC: Wake County Government, 1994) 12.

[9] Edward F. Stoddard, “Influence of the Falls Leucogneiss on the Human History of Wake County, North Carolina,” Paper No. 44-0, presented 5 April 2002. http://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2002NC/finalprogram/abstract_31150.htm, accessed 3 July 2007.

[10] Deposition of William Boylan, NC Archives, Misc. Records Wake County, C.R. 099.928.10 1838 -1849.

[11] Report by Robert Seawell, NC Archives, Misc. Records Wake County, C.R. 099.928.10 1838-1849.

[12] An example case of the debate over services provided by mills versus access to navigable waters can be found in Bourbon County, KY, when Laban Shipp applied for a permit to build a milldam and gristmill. An explanation of the events can be found in Stephen Aron, How the West Was Lost: The Transformation of Kentucky from Daniel Boone to Henry Clay (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996) 118.

[13] For an example of mill construction affecting fishing rights, see Harry L. Watson, “‘The Common Rights of Mankind’: Subsistence, Shad, and Commerce in the Early Republican South,” The Journal of American History 1 (1996) 13-43.