Chapter 3: Mills and Their Communities: Lassiter Mill and the Mill at Lake Myra by Leslie Hawkins Meadows

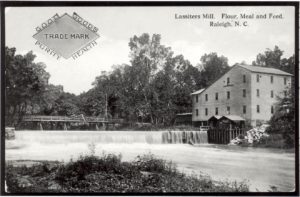

Lassiter Mill

John Giles Thomas began the construction of Lassiter Mill on Crabtree Creek in the early 1760s, around the same time Yates Mill was founded.[1] Thomas petitioned the Johnston County Court for permission to build a mill at the “Great Falls of Crabtree” in 1760. Then, in September 1764, Thomas acquired an acre of land from William Lindsay that was “condemned by order of Court of the said county for the use of John Giles Thomas, Esquire’s Mill on the north side of Crabtree Creek running down the courses of the creek.”[2] Finally, Thomas received the required permission from the Wake County Court in December 1771 to operate a public gristmill along Crabtree Creek.[3] Like Samuel Pearson, Yates Mill’s founder, John Giles Thomas was also an overseer for the roadways in Wake County; he was responsible for the maintenance of the road that led from the Wake County Courthouse to Crabtree Creek, which presumably ran near his mill. In addition to his gristmill, his farm, and his responsibilities for the roads, Thomas also operated an ordinary. Travelers to the Raleigh area needed places to stay and to board their horses; ordinaries offered lodging and taverns for food and drink. Thomas’ ordinary was conveniently located near what would become the state capital, helping promote business at his tavern.

In 1784, Isaac Hunter, Thomas’ son-in-law, purchased the mill property. Despite his extensive land holdings and several mills in the House Creek District of Wake County, Hunter is best known for owning an ordinary. His tavern was located on the main north-south road through North Carolina and it became a common stop for travelers on that highway. It was, therefore, well known to the delegates to the 1788 Convention selected to choose a “place for holding the future meetings of the General Assembly and the place of residence of the Chief Officer of the state.”[4] Until that time, the state of North Carolina did not have an official, permanent location for the General Assembly, the state courts, and the governor. The convention nominated seven locations throughout the state, including Isaac Hunter’s plantation and tavern, to the General Assembly. The General Assembly was to select the final location, at which point a separate commission would lay out the specific site, providing that it would be within ten miles of the place the General Assembly named. On the second ballot, the General Assembly decided Isaac Hunter’s tavern would be used to locate the new permanent state capital. The commission chosen to select the actual site of the capital met at Hunter’s house on 22 May 1792. Hunter likely hoped to sell some of his land to the state for the permanent capital. The state, however, ultimately bought 1,000 acres from Colonel Joel Lane for the location of the new state capital.[5] As a result, Hunter’s tavern ended up being four miles north of the State House. With that decision, Hunter’s tavern likely declined in importance for travelers and local residents because it was not centrally located to the new capital.

Hunter retained ownership of his grist and saw mills and ordinary throughout his involvement in the development of the City of Raleigh. The gristmill on Crabtree Creek burned in April of 1804, but was likely rebuilt soon thereafter.[6] Finally, in December 1813, Hunter advertised in the Raleigh Register his desire to sell his mills. His son-in-law, Durrell Rogers, purchased the mill at the Falls of the Crabtree in November 1819. From this point until when Cornelius J. Lassiter purchased the gristmill in 1909, the mill was known as Rogers Mill.

Durrell Rogers held onto the mill until his death in 1852; his will gave the mill to his son, Isaac. The mill then transferred to Isaac’s sisters in 1890 when he passed away. “I will and devise my entire estate of all kinds both real and personal to my four single sisters… jointly for the period of their several natural lives…. It is my will and desire that my estate shall be kept together for the benefit of all of my sisters until the last one dies, but should they at anytime desire to change any investment which I may leave they shall be at full liberty to do so.”[7] Because one of his sisters was widowed and the other three never married, Isaac wanted to make sure his sisters had every available means to support themselves as they saw fit. These sisters, however, did not operate the mill after Isaac Rogers’ death.[8]

The Rogers sisters sold the mill site to Wiley Clifton in 1894. Clifton planned to refurbish the mill and surrounding site, building a new set of businesses in addition to the gristmill.[9] Clifton, however, was unable to begin development of the property before he was forced to forfeit ownership when he defaulted on loans, for which he used the mill site as a security. Fabius Haywood Busbee, one of Clifton’s investors, purchased the mill at a courthouse sale in October 1901.[10] In 1907, Busbee sold the Rogers Mill site and four acres of land to Willis Whitaker, the owner and operator of Whitaker’s Mill, located just downstream from Rogers Mill. Whitaker, however, quickly turned around and sold the mill site to Cornelius Jesse Lassiter in 1908.

According to family legend, Cornelius Lassiter had been interested in owning and operating gristmills since his childhood. His mother had been widowed by the Civil War and had a difficult time providing for her family. As a result, she could only allow her children to have a biscuit on Sunday. The story claims that because of his love of biscuits and the desire to always have the money and supplies to make them whenever he wanted, Cornelius was determined to own his own gristmill. As an adult, Lassiter obtained a mill with a twenty-four-foot overshot waterwheel and a large lake for a water supply. In the mill, he had stones for grinding wheat, stones for grinding corn, and a cotton gin. He also had a store and sawmill nearby. In the market to expand his mill holdings, he then bought the Rogers Mill site on Crabtree Creek. The mill was no longer standing and only a portion of the dam was left. According to his daughter, Mary Lassiter, there was not even a road leading to the site any longer. “He took his own hands and built the road from Six Forks Road down to the mill and then on up to Glenwood Avenue, as far as Glenwood Avenue. So that’s why it was called Lassiter Mill Road. And I do not know whether it was called Glenwood Avenue at that time or not. But the intersection of what is now Glenwood Avenue and Lassiter Mill Road is St. Mary’s Street, was at that time called Lassiter Crossing.”[11] Lassiter was determined to create a successful milling business along Crabtree Creek, and to provide a way to get to the mill itself.

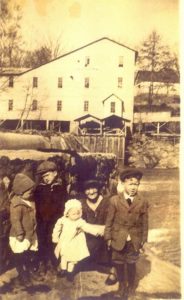

In addition to building the road, Lassiter built two houses on the site, and reconstructed the mill dam. Finally, he rebuilt the mill itself, with a lumber mill, a cotton gin, and stones for grinding both flour and corn meal. When all of that construction was finished, he built a boat house and purchased a number of boats for rental use. With all of the buildings completed, Mary Lassiter recalled, “He invited friends from every direction down to the mill, and it was quite a day. Friends brought picnic baskets for a big picnic. Boats were all over the creek and people were fishing.” [12] Lassiter wanted to offer a number of services at his mill to make his business as profitable as possible. He also recognized that renting boats and allowing fishing would make his mill more socially valuable to the Raleigh community. In addition, Lassiter generally enjoyed having Raleigh residents use the mill site as a recreational area.

C.J. Lassiter continued operating the mill until 1945, when he became ill and unable to work. At this time, his daughter Mary, son Lendon, and son-in-law Melville Wolfe, Jr. purchased the milling businesses. Three years later, Mary bought out Lendon and Melville’s shares in the gristmill business, and became the only female member of the North Carolina Corn Millers Association.[13] Mary Lassiter continued operating the gristmilling business on Crabtree Creek until a fire destroyed the mill in 1958. She did not, however, allow the fire to destroy the Lassiter Milling Company entirely. The gristmill on Crabtree Creek was never rebuilt, but Lassiter had other nearby milling companies continue to produce Lassiter Corn Meal according to her recipe. In this way, Lassiter Milling Company was able to continue serving its past customers and the local grocers throughout Wake County.

This system continued until 1971, when Lassiter sold her company to House-Autry Mills, Inc., in Newton Grove, North Carolina. She explained she had received offers from three different mills wanting to buy, “the Lassiter Corn Meal name, the machinery I had bought, the trucks… and the equipment I had. So, in 1971 I sold the business to the House-Autry Mill. They were going to continue to take care of our customers with Lassiter Meal, because I knew everybody wanted the Lassiter Corn Meal and I wouldn’t have let them down.”[14] Lassiter understood the Lassiter Milling Company customers enjoyed having a high-quality stone-ground product available locally; and, to her, House-Autry Mill was most likely to best provide for her loyal patrons. In a December 1970 letter written to all of her customers, Lassiter explained the sale,

House-Autry Mills, Inc. is the merger of old, experienced, and highly reputable milling companies and operates in a wide area of the state. The House-Autry Mills, Inc, will continue serving you as we have in the past, and we hope you will see fit to give them your continuing business.

It is our understanding that under the new management of House-Autry Mills, Inc. our customers will continue to receive the same high quality of both service and product.

I am deeply grateful to you for your friendship, confidence and patronage in the past and extend very best wishes to you and yours.[15]

House-Autry Mills continued selling cornmeal under the Lassiter Corn Meal name until the 1980s; today, all products are marketed under the House-Autry Mills name. After selling the gristmilling business, Lassiter continued to maintain her family’s interests at the site, and to operate the family’s small country store by Crabtree Creek until a fire destroyed the grocery building in April 1975.[16]

Mary Lassiter recognized the popularity of the mill site for picnickers, swimmers, and fishermen. The mill’s accessibility to those living in Raleigh made it one of the most popular picnic grounds near the city. In the 1920s, Susan Iden, a writer for The Raleigh Times, eloquently described some of the most popular pastimes found at Lassiter Mill, “Close by the stream are the dead ashes and burned out logs of many a camp fire; there are well worn foot paths through the woods and along the creek, and below the dam sand mounds where children have come to play and build their castles.… Bird lovers count it no hardship to forsake their beds in the early morning to go a-birding at Lassiter’s Mill.”[17] Unfortunately, as the spot became more and more popular, the public gradually stopped showing respect for the many privileges Mary Lassiter allowed them on her property. As she lamented in the early 1980s, “From the time my father built the mill until the time that I had to close it in 1975, we enjoyed having people come out and use the Lassiter Mill grounds, the beach, free of charge. But today I have to keep it closed because if I do not close it to the public there would be no supervision… I’m sorry that I have to keep it closed to people today.”[18] Lassiter closed the site to the public because of the amount of litter visitors were leaving behind, an issue visitors had been warned about repeatedly. A newspaper article announcing the changing policy at Lassiter Mill stated, “Miss Lassiter said she had gone to the area as many as three times a day to pick up litter. Some intruders, she said, had also broken her rules about drinking, cursing, and throwing people off the Lassiter Mill Bridge.”[19] At the time she closed her property, as many as 300 people a day were coming out to the site.

Today, growth in the city of Raleigh has surrounded the once calm, and even remote, Lassiter Mill site. What once was a quiet creek surrounded by woods, is now a housing subdivision in the midst of a growing metropolitan city. As early as the 1970s, members of the Wake County community pushed to make the Lassiter Milling property a Raleigh City Park so the city would accept responsibility for maintaining the site. Supporters of the proposal argued “Park value alone justifies city determination to keep up the Lassiter’s good work, but the property has historical importance, too.”[20] The mill site did not become a formal city park. In 1985, however, a quarter-mile segment of paved walkway was added to the Raleigh Greenway system, extending the trail to the old Lassiter Mill site. At the end of the trail are a plaque, millstone, and a piece of the old bridge that once crossed Crabtree Creek at the mill. The bridge was put there in the 1920s and it stood until the 1980s, when flood damage prompted the city to condemn it and tear it down. While none of the Lassiter Milling Company buildings still stand today, a portion of the site itself and the memory of the services provided by the mill are preserved thanks to the Greenway System.

The Mill at Lake Myra

The Lake Myra mill site was first developed by Thomas Price, Jr. around 1812. Price was a substantial landowner in the Mark’s Creek District of Wake County. Around 1808, he purchased 211 acres along Mark’s Creek that would be known as the Lake Myra mill site in the 20th century. By 1820, he had become one of the wealthiest landowners in the community; tax records showed him owning 2151 acres of land and 21 slaves. Also by 1820, he was not only operating the local country store, he was also the local banker, either lending neighbors his own money or endorsing their notes with the Bank of Newbern located in Raleigh. In addition, in 1823, he was appointed a justice in the Wake County Court.[21]

Price’s wealth and status in the Mark’s Creek and Wake County community was based on his agricultural, business, and commercial acumen. Price owned a total of five mills in Wake and Johnston Counties. Four of the mills were located in Wake County, three along Mark’s Creek and one on Buffalo Creek. The fifth was located on the Johnston County portion of Buffalo Creek. His sons also displayed Price’s talent for business, as well as his interest in investing in milling operations. His son, Washington, moved to Fayette County, Mississippi, where he managed extensive farming operations and three mills, including a gristmill, sawmill, and cotton gin. Price’s son, Needham, inherited approximately half of his estate, including two of the mills along Mark’s Creek. One of those mills, most commonly known as Price’s Mill, eventually became part of the Lake Myra property.[22]

Needham Price retained ownership of the mill until his death in 1870; his will left all of his property to his wife, Nancy Price, including land, stock horses, hogs, cows, mills, and household possessions.[23] Nancy Price’s will, executed in 1874, divided that property between their children and grandchildren, based on decisions she made with her husband before his death. Their daughter Mary Mangum, and her husband Priestly Mangum, were given about 1,150 acres of land, including “The Mill Tract” “and all the mills situate thereon, or on any part thereof, with the fixtures thereof, and all the privileges, appendages, and appurtenances thereunto belonging and used therewith.”[24] Mary and Priestly Mangum retained ownership of the property until at least 1878, because maps from that time period continue to identify the site as N. Price’s Mill.[25]

By 1887, Price’s Mill had changed ownership; Wake County maps list the site as being Hood’s Mill at that time.[26] W.H. Hood was most likely the next owner of Price’s Mill along Mark’s Creek; in 1884 and then again in 1890, he is listed as a mill owner in the Eagle Rock vicinity of the Mark’s Creek District.[27] W.H. Hood was possibly a member of the Hood family who owned and operated a small-scale family farm in the vicinity of the mill. This family is thought to have run a mill on Buffalo Creek during the antebellum period on their small plantation. W.H. Hood was also an ex-Captain in the Confederate Army, a county commissioner from 1891 to 1895, and the Register of Deeds for Wake County from 1898 until his death in 1901.[28] Little, however, is known about the mill’s operations, or development during its time as Hood’s Mill.

The timeline for ownership of the mill after the Hood family is not completely certain. A group of Raleigh doctors supposedly used the farmhouse once associated with the property as a clubhouse for several years during the 1920s, and the lake at this time was known as Doctor’s Lake.[29] Then, in the 1930s, a man named Stone developed the lake into the Lake Myra recreational complex, probably for the owner, Charles Woodall. Clarence Martin obtained the property from Woodall in 1939; he continued to operate the site as a recreational facility and is thought to have built the store, the pier, and the boat sheds at the site. Martin’s descendents continued operating the general store and allowing visitors to fish on the lake until the early 1990s.[30]

The gristmill continued to grind cornmeal until the 1960s, even though it was no longer the primary activity available for Wake County residents at Lake Myra, as more emphasis was placed on recreational use and the community store at the site beginning in the 1920s and 1930s.[31] At the complex, visitors could swim, fish, picnic, camp, and catch up on the local news. A newspaper article from 1934 advertises special attractions for the Fourth of July at Holt’s Lake and Lake Myra, two recreational facilities near the City of Raleigh. In the article, Lake Myra’s owner, Charles Woodall said the lake had enjoyed good crowds during the hot days in May and June. The article also reported, “Fishing is at its best there now. Lake Myra is comprised of 115 acres of clear spring water, surrounded by a woodland of beautiful trees. Bathing, fishing, boating, and picnicking are the popular pastimes there. Its proximity to Raleigh makes it popular as a picnic spot.”[32] Other newspaper advertisements also encouraged people to come out to Lake Myra for the Fourth of July, and listed some of the activities available, such as swimming and boating. One said “Spend July 4th Here, where it’s cool and inviting. We are prepared to take care of 5,000 people. Come early and stay late. Lake Myra is a safe beach for children and women.” The ad also mentioned having bathing suits and boats for rent, as well as a refreshment stand.[33]

The Lake Myra General Store remained open as late as the early 1990s, and visitors could go out on the lake to fish or “sit around the pot-bellied wood stove at the Lake Myra General Store and hear fascinating stories about the lake.”[34] Today, the gristmill, boardwalk, and boathouses at Lake Myra have all collapsed. Rubble is virtually all that is found where the gristmill once served area farmers and the recreational facilities once created a place of fun and relaxation for Wake County residents. The community store still stands, but has been closed since the 1990s. It stands next to the road, a silent reminder of all that once took place at that spot for those who drive by. The property is owned by a private family, but the Wake County department of Parks, Recreation, and Open Space is in the initial stages of planning a new County Park at Lake Myra to once again provide an area where residents will be able to go boating and fishing in the eastern part of Wake County.

Both Lassiter Mill and the mill at Lake Myra served their communities as active businesses for centuries. More important, and more memorable to recent Wake County residents, however, was the public’s use of the mill sites for recreation. Millponds and milldams create excellent opportunities for swimming, boating, and fishing. They are also scenic areas for picnics, dating, and parties, all of which the Lassiter family allowed on their property. These activities were encouraged even more at Lake Myra, where the lake was developed and marketed as a recreational facility. Because interest in old gristmills, mill dams, and local history remains, the Lassiter Mill monument on the Raleigh Greenway System and Lake Myra’s future with the Wake County Department of Parks, Recreation, and Open Space will continue to preserve those sites for public use.

[1] Much is known about Yates Mill and its owners because of extensive research and preservation efforts over the past 40 years. Yates Mill also benefits from being owned by a number of prominent Raleigh and Wake County residents who left a lot of information about themselves and their interests. Virtually all of Wake County’s custom mills would have created sites for fishing, swimming, and meeting one’s neighbors, like what was found at Yates Mill. However, very few of the custom mills that once stood in Wake County have a history that is so well known as Yates Mill because most mill owners and millers remained relatively anonymous in the larger Wake County record. While some of the early mills’ owners and their families were involved in the development of Wake County and the City of Raleigh, not all of the owners were as active in the larger community as their contemporaries at Yates Mill. The mills discussed in this chapter are even more well known than most because of the prominent roles they played in the social development of the Wake County community in the 20th century.

[2] Johnston County Deed Book 1, page 185 between William Lindsay and John Giles Thomas dated 24 September 1764. Wake County formed from Johnston County, Cumberland County, and Orange County in 1771.

[3] Elizabeth Reid Murray Collection, Business and Industry, Box 9, Folder 1, located at the Olivia Raney Local History Library, Wake County.

[4] Nov 11: Bill to Carry into effect ordinances for establishing a place for General Assembly meetings; Senate Bills 1788, General Assembly Session Records Nov-Dec, 1788.

[5] Ibid; Thornton W. Mitchell, “Hunter, Isaac” in Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, volume 3 ed. William S. Powell (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1988) 237.

[6] Raleigh Register and North-Carolina State Gazette 23 April 1804, page 3.

[7] Isaac Rogers 1890, Wake County Wills 1771-1966 Robeson – Rogers, Lydia W. C.R. 099.801.89.

[8] “Mill site has long history” Raleigh Times 14 August 1973.

[9] Elizabeth Reid Murray Collection, Business and Industry, Box 9, Folder 1, located at the Olivia Raney Local History Library, Wake County.

[10] “Mill site has long history” Raleigh Times 14 August 1973.

[11] Lynn Steven Brown’s recording of Mary Lassiter, ca. 1980. Transcript by Elizabeth Reid Murray. A copy of the transcript and a recording of the interview can be found in the Elizabeth Reid Murray Collection, Business and Industry, Box 9, Folder 1 at the Olivia Raney Local History Library.

[12] Mary Lassiter recording.

[13] Lynn Steven Brown, “Miss Mary Virginia Lassiter” in The Heritage of Wake County North Carolina ed. Lynn Belvine and Harriette Riggs (Raleigh, NC: Wake County Genealogical Society in cooperation with Hunter Publishing Co., 1983) entry number 458.

[14] Mary Lassiter Recording.

[15] Letter from Mary Lassiter to “All Customers of Lassiter Milling Company” 28 December 1970. A copy of this letter can be found in the Elizabeth Reid Murray Collection, Business and Industry, Box 9, Folder 2, in the Olivia Raney Local History Library, Wake County, North Carolina.

[16] Robert Lynch, “Suspicious Fire Destroys Last Part of Lassiter Mill” The News and Observer, 19 April 1975, 32.

[17] Susan Iden, “Lassiter’s Mill Place of Camp Fire Suppers and Picnics on Crabtree” The Raleigh Times 1927. A copy of this article can be found in the Elizabeth Reid Murray Collection, Business and Industry, Box 9, Folder 2, in the Olivia Raney Local History Library, Wake County, North Carolina.

[18] Mary Lassiter Recording.

[19] David Zucchino “Lassiter Swimmin’ Hole Falls Victim to Litter Bugs” The News and Observer 9 July 1975.

[20] “Lassiter Mill Deserves Park Status” The News and Observer 27 March 1974.

[21] “Oakey Grove, Wake County, North Carolina,” 5-6. Located in Elizabeth Reid Murray Collection, People, Price, Thomas, Box 34, Folder 14, in the Olivia Raney Local History Library, Wake County, North Carolina. This essay on Thomas Price was written by Elizabeth Reid Murray, based on her research on the history of Wake County and its residents.

[22] “Oakey Grove, Wake County, North Carolina” 1.

[23] Needham Price, 1870, Wake County Wills, 1771-1966, Powell, Henry Hinton – Proudly. C.R.099.801.

[24] Nancy Price, 1874, Wake County Wills, 1771-1966, Powell, Henry Hinton – Proudly. C.R.099.801.84.

[25] Map of Wake County Drawn from Actual Surveys by Fendol Bevers 1878, MC.099.1878b1.

[26] Schaffer’s Map of Wake County, 1887. MC.099.1887s1.

[27] Raleigh City Directory, 1883-1884, 596; Branson’s N.C. Business Directory, 1890, 663.

[28] “Capt W.H. Hood Dead” News and Observer 1 Feb 1901.

[29] Lally 225-226; Elizabeth Reid Murray Collection, Parks and Recreation, Box 9, Folder 3.

[30] Lally 226.

[31] Fred Bonner, “Old Lake Myra full of big yarns, fish” News and Observer 28 February 1988.

[32] “Lakes Planning for Big Fourth” News and Observer 1 July 1934.

[33] “Lake Myra: ‘Wake County’s Own Lake’” News and Observer 1 July 1934.

[34] Bonner.