The Last Mill Standing: Yates Mill by Leslie Hawkins Meadows

Pearson’s Mill, later known as Boylan’s Mill, Penny’s Mill, Lakewood Mill, and Yates Mill, was one of the first mills established in the area of North Carolina that would become Wake County. Through its long history, Yates Mill has seen thirteen different owners from eight different families, businesses, and institutions. Of the more than seventy mills once in operation in Wake County, Yates Mill is the only one that still stands. Without being in consistent use from its construction in the 1760s until the 1950s, and without the added interest in its preservation by its current owner, North Carolina State University, and community groups such as the Wake County Historical Society and Yates Mill Associates, it is unlikely the mill would have lasted so long. Recent preservation efforts and the mill’s continued existence are a testament to the mill’s importance in the development and history of Wake County.

The mill started in the early 1760s, probably around 1763, when the first owner, Samuel Pearson applied for a grant for the tract of land where the mill now stands. Pearson moved to the North Carolina colony from Maryland sometime in the early 1700s. He married his young wife, Mary, in 1748, when she was living with her parents in what was then Johnston County, North Carolina. In the early 1750s, Pearson purchased his first known tract of land in what would become Wake County. Pearson laid claim to and began the application process to receive the grant for the land where the mill now sits in 1763. However, due to events outside of his control, Pearson was unable to secure an official grant at that time. The Earl of Granville’s Land Grant Office closed after the Earl’s death later the same year, and failed to reopen before the beginning of the Revolutionary War in 1775. When the war began, the newly formed State of North Carolina seized British controlled lands. In 1778, North Carolina began issuing its own land grants. At that time, Pearson again requested a survey to be conducted on the same land he applied for in 1763. Pearson’s 1778 request for a land survey by North Carolina asked for “six hundred and forty Acres, lying in the County aforesaid [Wake], on the North side of Swift Creek and on the waters of Steep Hill Creek joining his own land on the South and West Side, Including his Mill Running… for Complement.”[1] This 1778 survey is the first known document to mention the mill’s existence and operation. By the time of his death in 1802, Pearson had gradually built a plantation of almost 1500 acres in Swift Creek.[2]

By bringing the first gristmill to the Swift Creek District, Samuel Pearson offered vital services previously unavailable to the new community. Before Pearson’s mill, settlers would have traveled much longer distances to have corn and wheat ground into meal and flour suitable for cooking. Visiting the mill would have also provided the new residents of the sparsely settled area a way to trade, learn the news, and meet each other to form both friendships and romantic relationships. Pearson himself also served his new and growing community in ways beyond running a farm and a mill. Samuel Pearson served in the Johnston, and then later Wake County militia. By 1772, he earned the rank of Captain, with 1 Lieutenant, 1 Ensign, 3 Sergeants, 3 Corporals, 1 Drummer, and 64 Privates under his command.[3] Part of his responsibilities included maintaining an eight-mile stretch of road between Walnut Creek and Swift Creek that ran past his mill. Because the location of mills often determined the location of roads and vice versa, Pearson’s road would have served a dual function in this new society. The road gave friends, neighbors, and customers a means to get to the mill, and helped Pearson’s business by directing people to his mill and the services he provided. His rank as Captain in the local militia is likely a symbol of his experience and the status he held in society. That status was due at least partially to the fact that he built the first gristmill in the immediate area.

Pearson’s will divided his property between his sons, and his daughters were to benefit from the sale of his personal property at a public auction. His son, Simon, was given “Three Hundred and forty Acres of land more or less lying on both sides of Steep-Hill Creek Joining Paris Pearson’s land, including the old Mill.”[4] Simon, however, would not be as financially successful as his father in managing the mill or his real estate investments. He acquired land, and loans, faster than he could pay for them. In the seventeen years between his father’s death in 1802, and 1819, Simon Pearson managed to purchase huge amounts of land, mostly from the tracts left to his brothers. He was thus able to create a farmstead of 1,500 acres in the Swift Creek District of Wake County. His large purchases, however, quickly put him into debt. In 1819, the State Bank took Simon and his business partners, Levi Jones, Southy Bond, and William Pope, to court to force payment on their defaulted loans. The judgment against Simon Pearson came down during the spring term of 1819, forcing him to pay $316.50 of his debt and costs, “of which sum three hundred dollars is principal.”[5] Pearson was unable to pay the fines, and the Bank confiscated all of his 1,500-acre property, including the mill, and sold it at a sheriff’s sale. William Boylan was the highest bidder, paying $3031 for the entire confiscated tract.[6]

Another wealthy Wake County businessman, who was also oriented toward public service, now owned the mill. In addition to owning his gristmill and significant amounts of land around Steep Hill Creek, Boylan acquired a total of three plantations in Wake County; he also invested in properties near Chapel Hill, in Johnston County, and in Mississippi. Boylan served as the second president of the State Bank, from 1820-1828. He was a charter supporter of the Raleigh Academy in 1801, and built the first county poorhouse. He served on the commission to build a new state capitol in Raleigh in 1831; and he established Raleigh’s first newspaper, the Raleigh Minerva in 1803, and later established the Raleigh Advertiser.[7]

Boylan’s interest in investment and the development of the Raleigh area likely prompted his purchase of the mill and the subsequent changes he made between 1820 and 1850. One of those changes was the inclusion of a sawmill, which tax records indicate was operating by the 1840s. The exact location of this sawmill, however, is unknown. Two potential locations have been identified – the shed that was attached to the mill at a later date, and the abandoned dam found near the mill also on Steep Hill Creek – but neither has been confirmed as the actual location. This additional service would have made the mill more valuable to the community, because residents could now have lumber produced or purchase lumber from a local source, rather than having to have it shipped from other mills in Wake County, or from elsewhere in North Carolina. Travel at this time was still slow and difficult, so even though other mills in Wake sawed timber for the county’s residents, including the mill owned by Durrell Rogers on Crabtree Creek, having a sawmill close by would have been appreciated by area residents and possibly would have made Boylan’s Mill more attractive to potential customers who used other gristmills.

Boylan owned the mill for 37 years before selling it to James Penny, John Primrose, and Thomas Briggs on 30 June 1853. Boylan sold approximately 1,900 acres, as well as the grist and saw mills, possibly to pursue different interests.[8] Primrose kept his share of the mill and land for only six years before selling his share to James Dodd in 1859. Penny, Briggs, and Dodd then retained ownership until 1863. After the initial purchase in 1853, the mill was known as Penny’s Mill. It retained this name even after it entered the Yates family in 1863 to avoid confusion, because the Yates family also owned a mill located on Walnut Creek.

Like their predecessors, Penny, Briggs, Primrose, and Dodd managed the mill and benefited from its operation financially, but did not run it themselves. These men generally concentrated on other business, and political interests in Raleigh, Wake County, and the South as a whole. For example, James Dodd and Thomas Briggs were both contractors in Wake County and had a shared interest in a hardware store in downtown Raleigh. The sawmill operations Boylan added during his ownership likely attracted Dodd and Briggs to invest in Boylan’s mill. John Primrose concentrated more on financial investments. For instance, he was one of the local directors of North Carolina’s first insurance company, North Carolina Mutual Fire Insurance Company.[9]

While many owners of local, custom gristmills likely would have operated their mills themselves, most of Yates Mill’s owners were wealthy and prominent enough to be able to pay someone else to run the mill for them. Penny, Briggs & Co. advertised for a miller in the Raleigh Register in 1858: “MILLER WANTED, TO ATTEND TO our Mills; five miles southwest of Raleigh. None need apply who is not of good moral character. Our terms are liberal.”[10] Unfortunately, the identities of the millers who worked at Yates Mill are largely unknown because local gristmills, operating through the miller’s toll and barter, often did not keep formal records of employees, or how much grain was ground.

The mill owners’ interests did not stop with business concerns; Briggs and Penny were both active in the secessionist movement. When war broke out in 1861, Penny decided to join the fight, leaving his wife to manage the mill’s business. Since he owned the mill rather than operating it, the North Carolina laws prohibiting mill operators from joining the military did not bar Penny from fighting. During his absence, Hinton Franklin, a mill customer, ran up a $700 debt to the mill. When Penny came home on leave in 1863 and discovered the huge debt, he went to confront Franklin and collect the money. According to local legend, a fight ensued. The Penny family claims Franklin struck first, hitting Penny across the face with a whip, and that Penny carried a scar from that attack for the rest of his life. Regardless of who initiated the fight, Penny hit Franklin repeatedly in the head, neck, and face with a stick approximately two inches thick. Franklin’s wounds proved to be fatal.[11]

The legend then claims that when Sherman’s troops reached Raleigh late in the Civil War, Franklin’s widow told them that her husband’s death was due to his Northern sympathies, not his debt, prompting Northern troops go to Penny’s Mill and attempt to burn it down. Neighbors discovered the fire and managed to extinguish the blaze before the mill was damaged. Very little evidence exists of the attempted fire other than a charred beam found underneath the entrance porch during restoration efforts. Penny’s legal troubles in 1863 possibly prompted the sale of his mill to his future son-in-law, Phares Yates (Phares married Penny’s daughter, Roxanna, in 1866[12]). Yates did not purchase the entire tract of land from Penny, Briggs, and Dodd. He acquired only the grist and saw mills and 94 acres surrounding them.[13] Penny sold his share of the remaining 1788 acres of the joint property to Briggs and Dodd in 1864, also possibly because of his legal troubles during the Civil War.[14]

After Phares Yates bought the mill in 1863, he was the first of four generations in the Yates family to own the mill on Steep Hill Creek. In addition to maintaining the grist and saw mill businesses, Phares also likely added wool carding to the list of services offered at Penny’s Mill. North Carolina at this time was still a state of small farmers living in small settlements. Raleigh was a growing city, but it was still mostly surrounded by small farms that produced enough food and other household supplies to fill most of their needs. By offering the greatest number of services at one stop, such as a gristmill, a sawmill, and a wool carder at one site, the mill would become more financially viable and successful, as well as more valuable to the community as a whole. Some local residents claimed the mill carded wool for uniforms for North Carolina during the Civil War. However, no business or tax records list wool carding as a service provided by Penny’s Mill prior to Phares Yates’ acquisition. In addition, the wool carder currently on the second floor of the shed inside the mill has a patent date of 1869. As a result, it is unlikely that Penny’s Mill was involved in carding wool for the Civil War effort.

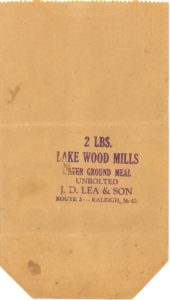

Upon his death in 1902, Phares Yates’ will left the mill and 199 acres to his son, Robert Edward Lee (R.E.L.) Yates, and stipulated that Roxanna “have half interest in the said Mill during the term of her natural life.” Phares also left Roxanna the house and 156 acres so she would be able to continue to live comfortably. [15] In addition to owning his father’s mill and running a dairy farm in the Swift Creek Township, R.E.L. was a math professor at North Carolina State College. He named his dairy Lakewood Farms, and the mill Lakewood Mill. It was during R.E.L.’s ownership that the mill started scaling back on its operations. The mill no longer produced lumber or carded wool. John Daniel Lea, Sr., the last miller, is known to have ground corn throughout his tenure as miller. It is possible that in the early years Lea also produced flour at Lakewood Mill; but, as the machinery started needing repairs and replacements, he cut back to simply grinding cornmeal. His daughter, Mary, stated in an oral history interview that he ground “cornmeal and he would grind graham flour and it made good biscuits, real good, a lot of people loved it, liked it…. Did that for a while and then it kind of, you know, give out, it had to have some work done on it and they stopped doing that [producing graham flour].”[16] Despite the cut back in production, Lea continued to produce cornmeal for anyone who wanted it, and sell the meal he produced from his miller’s toll to local grocers, throughout his service as the miller from 1898-1953, when the mill closed.

When R.E.L. passed away in December 1937, he left the mill, as well as all his other “real and personal property” to his wife, Minnie John Yates.[17] Minnie shared ownership of the mill with their son, Wilbur, for ten years. In 1947, one year before Minnie’s death, they sold the mill to the Trojan Sales Company, a subsidiary of A. E. Finley Associates, a construction equipment distribution company. Finley had been interested in the mill and the millpond for several years before the actual purchase from the Yates family. Finley visited Lea and took boats out on the pond starting in 1943. Those visits likely piqued Finley’s initial interest in the site, providing him an opportunity to see how a site like that could be used as a retreat area close to the city for company employees. Dick Thompson, a former employee of A. E. Finley, described the purchase, “it was in early 1947 we were back out here, I know it was cold weather, and Mr. Lea said something about Wilbur Yates, that was Mrs. Minnie Yates’ son, and Professor R.E.L. Yates’ son. Said something about Wilbur might want to sell this thing, the mill, the millpond… And it wasn’t long before they, you know, we got in touch with Wilbur and then Mrs. Yates and they arrived at a price… that was in early 1947.”[18] Later that year, the Trojan Sales Company transferred the property to the North Carolina Equipment Company, another A. E. Finley Associates’ subsidiary. After that transfer, the North Carolina Equipment Company would retain ownership of the land as long as the A. E. Finley Associates owned the property.

E. Finley Associates were also active at the site. Finley purchased neighboring lands, creating a 1,007 acre property. On that property Finley’s employees ran a cattle ranch and an orchard. Finley also designed and had a retreat lodge constructed near the mill. Dick Thompson explained that the lodge was initially built for “business purposes mainly, because that’s where we would hold sales meetings and service meetings and that sort of thing. And see we operated all the way from Norfolk to Miami and we’d bring all those people up… for meetings and also our service personnel would bring them in here for meetings… and I guess the idea of it being used for civic people and churches and personal use was sort of secondary to the main reasons.”[19] In addition to the lodge, the facility also included picnic tables, fire pits, and even a shuffleboard court for recreation. As a result, Finley employees and area residents alike could continue gathering at the mill for both work and play, even after the mill closed.

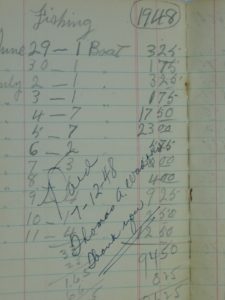

Even with its new, corporate owner, Lakewood Mill continued its custom mill operations serving the local, Wake County population until 1953. Area residents came out to the pond to fish, swim, and go boating. As an additional source of income, Lea built rowboats, and charged visitors who wished to fish or use a boat on the pond. Mary Lea Simpkins recalled that her father rented the boats for day, “It could have been 75 cents a day and they could fish as long as they wanted to.”[20] Much of the money Lea earned by renting the boats went to the mill’s current owner, either the Yates family or A.E. Finley Associates, as rent for the mill and pond. A. E. Finley Associates continued to host meetings and to allow company and family gatherings at the site throughout the 1950s.

Yates Mill Pond was also used by local churches for baptisms until the 1950s. Because churches and gristmills were generally built nearby to provide for the same communities, millponds traditionally served as typical locations for baptisms. Inwood Baptist Church, located just down the road from Yates Mill, had used the nearby millpond for its baptismal service since the church’s establishment in 1877. Inwood stopped using Yates Mill Pond for baptisms in 1952, but several members of the church remember being baptized in the millpond.[21] Mary Lea Simpkins recalled being baptized in the mill pond at the age of thirteen, “when they had a baptizing, everybody would come…. I was baptized there and several other people at the same time.”[22]

Lea closed the mill in 1953 after nearly two hundred years of service because fewer people came to have meal ground as the number of local, small farmers dwindled and consumer preferences changed to store bread and bleached white flour. Lakewood Mill could not compete with national merchant mills using new technology to supply Raleigh grocers with a more desirable product. And, as Mary Lea Simpkins said, “I guess there’s not as many farmers, you know, as there was.”[23] Despite the mill’s closure, local residents continued fishing and swimming in the pond. And the mill certainly would have remained a scenic spot for picnics and for young adults looking for a romantic place to date.

In 1958, two students from the NC State School of Design, Max Evans and Robert Cole, made detailed drawings of the mill equipment and the waterwheel’s construction. Those drawings would become invaluable several decades later during the restoration process, because years of rust and decay, as well as generations of use, left the mill and its machinery in complete disrepair. It was not until 1963, however, that North Carolina State College (it became North Carolina State University in 1965) assumed ownership of the mill. At that time, the school purchased the 1,007 acre property from the North Carolina Equipment Company and A. E. Finley Associates to develop into research farms for the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS). The mill was included in this purchase, but it was not considered a focal point of the property because no one was sure what to do with it. Lea supposedly ran the mill one last time shortly after NC State bought the mill as a demonstration.

Because NC State recognized the historic importance of the old mill, the school was interested in the future of the mill and in finding a way to appropriately use and preserve the historic site. One of the first actions taken by the school was to rename the millpond. In 1964, Carroll Mann, Jr., Director of the Office of Business Affairs, Facilities Planning Division, wrote to Chancellor John Caldwell,

It has come to my attention that the U.S. Geological Survey has made inquiry concerning the official name of the lake, on the Finley Farm property which we recently acquired.

In recent years this lake was renamed Trojan Lake, or Lake Trojan by the North Carolina Equipment Company when they acquired this property. This name, I believe, was derived from one of their subsidiary companies, the Trojan Sales Company.

The lake, and surrounding property was for many years in the Yates family, and Professor Yates… was a member of our faculty in the Mathematics Department for many, many years….

As long as I can remember, and up until it was recently renamed, this lake was always known as Yates Mill Pond. The old mill is still there.

It is my recommendation that we reinstate the original name, and that this lake be now known officially as “Yates Mill Pond.”[24]

Chancellor Caldwell agreed, and as a result, the mill and its pond were both renamed Yates Mill in honor of the last family to own the mill.

By the late 1960s, the mill was beginning to fall into poor condition and required significant repair and restoration to be operable again. The school took some initial protective measures, such as putting a new roof on the mill to help prevent further deterioration, and building a fence to keep some potential vandals out. Because of the diverse services the mill provided while in operation, “interest in preserving the mill has been expressed by people in several NCSU schools, including textiles, forest resources, agriculture, and design.”[25] Each of these departments saw the mill as a potential tool to educate their students in the history of their programs and industries. More significantly, in 1974, an architecture class from the NCSU School of Design taught by Donald Barnes took a special interest in Yates Mill, making a set of detailed architectural drawings of the mill and the machinery inside.

In 1974, the students and Dr. Barnes also started research on Yates Mill’s history, including conducting an interview of Hugh Champion, a nephew of Mr. Lea, who told the students that a blacksmith shop once stood across the road from the mill. Based on that interview, the students wanted to reconstruct the blacksmith shop in the mill yard and then use it to launch the full restoration of the mill. The students located a portion of an old tobacco barn that was going to be flooded over during the construction of Jordan Lake, and arranged for that barn to be moved to Yates Mill. This recycled tobacco barn was supposed to be the students’ blacksmith shop. The university did not have the funds, however, to financially support the restoration, and so the project did not go forward. Dr. J. Lawrence Apple, the director of the Institute of Biological Sciences in the School of Agriculture and Life Sciences, admitted in 1971, “‘The University cannot spend public money on the mill. At least $100,000 would be required to place the mill and machinery in operating condition. Another $50,000 to $75,000 would be needed annually to maintain and operate the mill as a public attraction.’”[26] As a result an outside group would be needed to raise the funds necessary to care for Yates Mill.

The restoration of the mill would require significant funding and a long-term commitment of time and energy, neither of which the established historical groups in Wake County had in any quantity. These problems were compounded by the fact that a large mill restoration project was not central to the missions of any of the existing groups. Thanks to the initial interest and work of the Wake County Historical Society and NC State University, which teamed up in the late 1980s, fund raising efforts to preserve Yates Mill began. Then a group of volunteers created an organization whose sole concern was the restoration and continued preservation of Yates Mill. Community members established and incorporated the Yates Mill Associates (YMA) as a non-profit organization in July of 1989.[27]

In 1996, YMA, in partnership with NC State University, Wake County Parks, Recreation, and Open Space, and the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, developed a plan for a 176 acre park. Wake County leases the property from NC State University and manages the day-to-day operations of the park; NC State, as owner of the property, continues to have access to the facilities at the park for research; and YMA is responsible for interpreting the mill, as well as the continuing maintenance of the mill. Having so many groups interested in the preservation of the mill and the recreational activities at the site has insured enough long-term support for the project. However, each group also has specific responsibilities that are not always aligned with each other. Wake County has to provide programming and services to the public that go beyond the mill site; NC State has to preserve enough of the site for future research projects on natural resources; and YMA needs to continue active fundraising to provide for the ongoing preservation of the mill.

Restoration of the mill and development of the park faced a serious setback in the fall of 1996, when flooding from Hurricane Fran breached the original dam, drained the mill pond, and destroyed the shed. The hurricane, however, helped increase awareness of the impending threats to Yates Mill and the gristmilling traditions in Wake County. Ten years after park planning began, Historic Yates Mill County Park finally opened to the public in May 2006. The centerpiece of the park is the historic mill; yet, the park has also enabled the mill to once again serve as the center of its community by providing hiking trails, picnic areas, a visitor center with an exhibit hall and research facilities, fishing on the pond, tours of the mill, and other educational programming for the public. Because of the committed members of YMA who refused to watch Wake County’s last remaining gristmill fade into history, and the members of the community who once again utilize and enjoy the opportunities for fun and education, Yates Mill continues to serve in its role as a community center, a role it has filled for 250 years.

[1] Request for a Land Survey Issued 9 August 1778, Entered 15 July 1779, Book 38, No. 85, North Carolina Archives. Pearson acquired his first known piece of land in Swift Creek when he entered a Warrant for a land survey on 4 April 1756.

[2] Samuel Pearson Will, June 8, 1802, Wake County, North Carolina, Will and Estate Records, Clerks Office, Book G, page 1.

[3] Murtie June Clark, Colonial Soldiers of the South, 1732-1774 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1983) 828.

[4] Pearson Will, 1802.

[5] Judgment Against Simon Pearson, Minutes of Superior Court Docket, Spring Term 1819, page 23.

[6] Sheriff’s Sale from Simon Pearson to William Boylan 1820, Wake County Register of Deeds, Book 3, page 384.

[7] Murray 113, 252, 272; Sarah McCulloh Lemmon, “Boylan, William,” in Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, Volume 1, A-C, ed. William S. Powell (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1979) 205.

[8] Sale of Mill from William Boylan to Primrose & Briggs 1853, Wake County Register of Deeds, Book 20, page 185.

[9] Murray 273.

[10] Advertisement, Raleigh Register 31 July 1858, page 2.

[11] Manslaughter Indictment of James Penny 1867, Wake County, Minutes, Docket of Superior Court 1852-1871, 2 vol., pages 521-523.

[12] Marriage License between Pharis Yates and Roxanna Penny 1866, Wake County Wills and Estates.

[13] Sale of Mill from Briggs, Dodd, & Penny to Yates, 1863, Wake County Register of Deeds, Book 8, page 652. While the original transfer of land took place in 1863, it was not registered with the Probate Court and the Office of the Register of Deeds for Wake County; see Wake County Book 28, page 652-653, 23 November 1869.

[14] Sale of Land to Briggs and Dodd by Penny, 1864, Wake Count Register of Deeds, Bok 24, page 318.

[15] Will of Phares Yates 1893, Wake County, Register of Deeds, Wills and Estates, Book E, page 69. The will was registered in 1893, but was not executed until Phares Yates’ death in 1902.

[16] Simpkins Interview 2001.

[17] Will of Robert Edward Lee Yates 1929, Wake County Register of Wills. The will was originally a handwritten copy without a witness’ signature and was found among R.E.L.’s papers after his death. His children, Wilbur, Elizabeth, and Gladys attested the handwriting as belonging to R.E.L. after his death in 1937.

[18] Oral History Interview of J.D. “Dick” Thompson, conducted by Rebeccah Cope and Sarah Rice, 26 July 2005. A transcription of the interview is located at Historic Yates Mill County Park.

[19] Thompson Interview 2005.

[20] Simpkins Interview 2001.

[21] Roger H. Crook, Living Stones: A History of Inwood Baptist Church (Columbia, SC: R.L. Bryan Company, 2000) 77.

[22] Simpkins Interview 2001.

[23] Simpkins Interview 2001.

[24] North Carolina State University Special Collections, University Buildings, Sites, and Landmarks, 1888-2005, UA 050.004, Box 9, Folder 11: Yates Mill, 1964-1997.

[25] Tom Byrd, “NCSU Seeks Means to Save Historic Yates Mill,” The Journal of North Carolina State University, 9 (1971) 1-2.

[26] Byrd 1.

[27] From a letter calling for individuals to join the Charter Board of Directors for Yates Mill Associates. A copy of the letter is located in the folder, History of YMA, located in the offices of Historic Yates Mill County Park.