Conclusion by Leslie Hawkins Meadows

Every custom gristmill served its local community and encouraged that community’s growth and development. Mills provided a food source; mill ponds were baptismal fountains, fishing spots, and swimming holes; mill yards offered space for community members to meet, talk politics, trade, and even date. Many mill owners discovered that mill sites could turn a profit from more than grinding grain; as was the case at Yates Mill, Lassiter Mill, and the mill at Lake Myra. Gristmills often had a saw mill operation or a distillery associated with the site as an additional service and source of income. Blacksmiths and general store owners often found mill sites a convenient and profitable location. Encouraging the social uses of the millpond – for swimming, boating and fishing – often helped generate additional income for the millers. Mary Lassiter especially understood how important her mill site was to the citizens of Raleigh for recreation, and she wanted to keep the area open free of charge to the community, even after the mill shut down. Only when cleaning the area became too much of a burden did Lassiter close the site to the public.

In conversation with friend Lynn Brown, Mary Lassiter often described Lassiter Mill as “a photographer’s dream, a lover’s paradise, a fisherman’s ideal, a scenic attraction, a spot dear to the hearts of children, a place of fond memories for the aged, a haven for relaxing in the sun, and a treasure of natural beauty for all.”[1] While Lassiter certainly would have been most familiar, and pleased, with these roles her mill played for Wake County, Yates Mill and Lake Myra would have offered the same sort of benefits to the community. But rarely were recreational activities at the mill formally organized as they were at Lake Myra. Community use and development around the mill site were generally based on an understanding between the mill owner, the miller, and the mill’s neighbors. As a result, most of the knowledge people have today of these many uses comes from the collection and interpretation of oral histories, local traditions, and community histories, making the research of the mill’s community and understanding all the roles the custom mill filled more difficult. The research challenges presented by the lack of official documentation, however, do not make those roles any less significant.

Before the establishment of the City of Raleigh in 1792, Wake County was simply a collection of local, individualized communities without a permanent town or county seat. Gristmills, ordinaries, and churches would have located themselves throughout the county to serve the varying needs of each local community and the travelers passing through. These individual communities would have been largely self-sufficient without a central town to attract local, regional, and national trade to promote economic growth. As a result, gristmills and their associated businesses such as distilleries, sawmills, and general stores provided a number of services that were not easily replaced until the later development of a full market economy in the city of Raleigh. Until the 20th century, travel by horse and wagon to the mill was still difficult, so having easily accessible gristmills and other community services throughout the county would have remained important. As Raleigh and Wake County began to rapidly grow and develop after the Civil War and Reconstruction, and as higher quality products could be more easily transported from across the country to area residents, the local, custom mills gradually began to shut down. Over time, all of Wake County’s more than 70 gristmills closed for business.

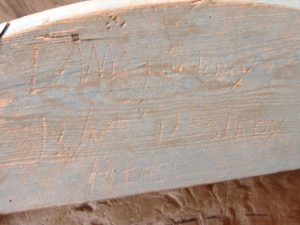

Before the days when parks and greenways showcased and protected old mill sites, neighbors continued to understand and appreciate the historic significance of the local gristmill to Wake County. The above picture was taken inside of Yates Mill and is but one example of the graffiti found inside the building. Perhaps, however, it is one of the most revealing markings. The source of this carving is unknown; presumably it was done by someone who broke into the mill after it closed. Ironically, even though the carving was an act of trespass and vandalism, whoever left it clearly understood the value of the old mill, and wanted to insure that the mill and its machinery were left for future generations to see, learn from, and enjoy. Looting after a mill closed was common practice because the wood and machinery parts inside could be used construction elsewhere. The materials could have been used to build a new mill or other business, and the gearing could be transferred to another industry. Use and reuse were common themes while a mill was in operation, and people would see no reason for the materials in the mill to go to waste as it slowly disintegrated.

A descendant of the Borland family, a milling family in Orange County, North Carolina, “philosophizes about the old days of watermills: ‘It would be difficult … to assess the impact of these old mills over the years. I hold with the belief that they had a great and good influence… on the opening up and development of communities.’”[2] In fact, local mills gave people a place to meet and to exchange ideas on politics, morals, and religion. They also provided places for fishing, picnics, boating, and dating. These various social functions of the mills were probably not in the front of the minds of their builders or their patrons. Mill owners were often more concerned with financial gain and providing an economic service to the region; for them, the social and communal aspects of the gristmill were of secondary importance. The farmers who used the mills enjoyed having a convenient food source for their families, but also utilized the other services and activities available at the local gristmill. In retrospect, “all who lived in the days of watermills acknowledge the wider role that mills played in their lives: the excitement, the pleasure, the stimulation to growth of mind and sociability, and to a sense of identity and membership in a community and in a nation.”[3] Few of the structures still stand, but the foundations, dams, and millponds that remain continue to evoke feelings of excitement and wonder to visitors and past patrons alike.

Today, the local, custom mills no longer serve their economic purposes. Without constant use, most have disappeared from the landscape. As the mills in Wake County continued disappearing, the residents of Wake County decided it was time to take action to preserve one of the few remaining structures and the memories of the gristmills that once stood. The fully restored Yates Mill, the historic markers at the Lassiter Mill site, and similar preservation efforts at mill sites across the country, are all physical representations of nostalgia for past businesses and communities, and all help preserve the legacy of gristmills and the local communities they once served. Most of the physical remains of the mills in Wake County have disappeared, and the memory of water-powered gristmills in operation is quickly fading as well. Only through the preservation of the memories of the county’s gristmills will Wake County residents be able to continue to understand the economic and social importance of gristmills in the county’s, state’s, and nation’s development. The mills, the machinery, and the dams that remain are silent reminders of what were once thriving industries and communities that built the city and county we know today.

[1] Brown entry number 458.

[2] Anderson 33.

[3] Ibid.